|

Planetary health - Is a two degree target really the correct indicator and target of planetary health?

Credit: Victor and Fennel 2014.

|

A comment posted on my Paris climate conference

introductory blog asked whether I believed COP21 has set itself up to fail with its target to keep global warming below 2°C. This blog aims to provide an answer, questioning why 2°C been chosen as the target?

Despite the

controversy of COP15 in 2009, the

Copenhagen Accord included for the first time the long-term goal of limiting the maximum global average temperature increase to no more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels putting a number on what constituted the limit for dangerous climate change.

According to all the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessed emission scenarios, surface temperature is projected to rise over the 21st century (fig.1).

|

| Global average surface temperature change from 2006 to 2100 relative to 1986-2005. |

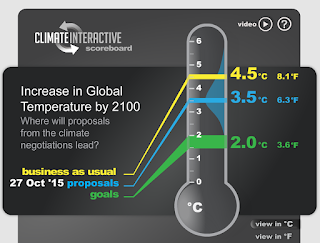

The increase in global mean surface temperature by the end of the 21st century relative to 1986–2005 is likely to be 0.3°C to 1.7°C under RCP* 2.6, 1.1°C to 2.6°C under RCP 4.5, 1.4°C to 3.1°C under RCP 6.0 and 2.6°C to 4.8°C under RCP 8.5 (

IPCC 2014). Without any additional mitigation efforts beyond those in place today warming is more likely than not to exceed 4°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

|

Risks from climate and temperature

range for five reasons of concern. |

Five Reasons For Concern (RFCs) aggregate climate change risks and illustrate the implications of warming and of adaptation limits for people, economies and ecosystems (IPCC 2014).

Figure 2 shows these RFC's. The risks associated with temperatures at or above 4°C by the end of the century (>1000 ppm CO2) include substantial (very high/high) species extinction, global and regional food insecurity, consequential constraints on common human activities and limited potential for adaptation in some cases. Some risks of climate change, such as risks to unique and threatened systems and risks associated with extreme weather events, are moderate to high at temperatures 1°C to 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Yet 2°C is still the target of COP21.

The IPCC have found cumulative emissions of CO2 to largely determine global surface warming by the end of the 21st century and beyond meaning significant cuts in emissions over the short term can substantially reduce risks of climate change over the longer term.

Table 1 shows that emissions scenarios leading to CO2 equivalent concentrations in 2100 of about 450 ppm or lower are likely to maintain warming below 2°C (IPCC). However, this requires 40 to 70% global anthropogenic GHG emission reductions by 2050 compared to 2010, and emissions levels near zero or below in 2100. Interestingly scenarios which more likely than no limit warming to 1.5°C by 2100 are characterized by concentrations below 430 parts per million (ppm) CO2 by 2100, and 2050 emission reduction between 70% and 95% below 2010. Scenarios of greater than 1000 ppm CO2 make it almost impossible to limit global warming to less than 3°C.

|

| Key characteristics of the different temperature scenarios showing the necessary emission reductions and relative likelihood. |

2°C would be a massive milestone in curbing global warming requiring dramatic reductions in green house gases. Yet, somewhat hidden by the aura of the 2°C target and shown by

figure 2 is that even two degrees may be too high. As argued by climate activist David Spratt a 2°C is a "very unsafe target" marking instead the boundary between dangerous and very dangerous climate change. Even though the IPCC adopt the 2°C target these views do appear to be echoed by the IPCC findings (fig. 2). As a recent

Guardian article argued, if global warming is limited to 2°C, warming will still destroy most coral reefs and glaciers and melt significant parts of the ice caps. Even under RCP 2.6 sea level is still expected to rise 0.4 (IPCC 2014). An even lower target is needed. Back in 2008 it was argued that an atmospheric CO

2 target of at most 350 ppm is required (

Hansen et al), 100ppm lower than the requirement of the 2°C target. "We should therefore be striving to limit warming to as far below 2°C as possible. However, that will require a level of ambition that we have not yet seen.” (Professor Chris Field of Stanford University in Guardian article).

Not only does the 2°C target not appear significant enough there have been calls in Nature for the target to be ditched and replaced (

Victor and Fennel 2014), arguing the target is "politically and scientifically... wrongheaded".

They argue that politically it has allowed governments to pretend they are taken action when in reality they are in fact they are achieving very little. Chasing this goal has allowed governments to ignore the need for massive adaption to climate change. I for one presumed (wrongly) that the 2 degree target specified for COP21 and repeated like a manta, cited thousands of time in newspapers, journals and even in the IPCC report was sufficient enough to limit warming. Only looking at the evidence has shown me otherwise.

Victor and Fenell also argue the target is "effectively unachievable" citing feasibility and cooperation. Again evidence supports this. In September last year PwC issued a

report arguing that there is a "disconnect between the global climate negotiations aiming for a 2°C limit on global warming, but national pledges may only manage to limit it to 3°C, and current trajectory actually on course for 4°C." This is echoed by

analysis of the INDCs (climate pledges) put forward by 146 countries in the lead up to COP21 released last week which suggest that the pledges will only reduce warming to 2.7°C by 2100. However are these really reasons for why a 2°C target should be scratched? Are they not just reasons for more action?

Scientifically they suggest the basis for the

2°C goal is "tenuous" arguing that a single index of climate change is impossible calling for a set of indicators to gauge various forcing and stresses. The Planetary Boundaries framework (Steffan et al. 2015) is a clear example of such an approach assessing and defining a safe operating space for humanity based on 9 'Planetary Boundaries'. That said the 2°C is not really just single metric, it is closely linked to a multitude of risks (

Schellnhuber 2014). The IPCC for instance have outlined the GHG emission reductions required to reach the target. Instead, a 2°C goal creates an easily comprehendible bench mark with more complex indicators behind it.

I agree with Victor and Fenell that a new of set of planetary indicators needs to be developed and should become the basis of climate policy - over time. As the limitations of the Planetary Boundaries Framework show such an approach is not yet ready to take the batten. I certainly do not agree that COP21 should be a technical conference developing such metrics as they suggest. Although their article sets out to tackle inaction, debating metrics just creates more distraction when COP21 really is crunch time.

Moreover in terms of communicating the importance of a deal in Paris to the governments and public a 2°C target has much more weight. In

response to the article Hans Joachim Schellnhuber (Angela Merkel's climate advisor) says "I am communicating to heads of state and you have to keep it neat and simple. It was difficult enough to commuicate a 2°C target ... but it seems to have sunk in. How should I communicate to policy makers who have an attention span of 10 minutes a set of volatility signals … this is politically so naive”. However imperfect, a target that is sinking in and generating change is better than overly complicated incomprehendible one.

I do not believe COP21 has set itself up to fail with its target to keep global warming below 2°C. The target appears to have created an understandable metric promoting people, businesses and governments to respond to climate change in a way not previously experienced. The metric is not a long term solution. A new set of internationally recognized planetary indicators should be be agreed upon, but 2°C will suffice for the time being and overall metrics will always have a role to play. However, COP21 is setting itself up to fail the planet by only providing half the answer. 2°C global warming is still too high. We must strive to limit warming as far below 2°C and this should become the focus of international climate policy. The target is not enough, but it is better than nothing.

*RCP = Representative Concentration Pathway. A set of four scenarios identified by their approximate total radiative forcing in year 2100 relative to 1750: 2.6 W m-2 for RCP2.6, 4.5 W m-2 for RCP4.5, 6.0 W m-2 for RCP6.0, and 8.5 W m-2 for RCP8.5 (IPCC 2013).